The solitary self is becoming an unfamiliar place we would rather not visit.

We can all celebrate the expansion of information made possible by the internet. But there is a price to be paid for total connectivity, especially the portion of it that drops into the black hole of phone culture. The ability to call or receive messages from people we know or public figures we ‘follow’ takes a heavy toll on the energies of addicted users. It’s becoming a familiar complaint.

Notice what people are doing when they are caught in a pause between activities: maybe waiting for a train, a friend, or the start of a meeting. They are usually in the thrall of their devices. Any pause in the day must be filled with the search for an incoming distraction. The solitary self is mostly an unwelcome place we would rather not visit. True, a person could be reading a provocative book on their device. But it is far more likely they are cleansing their phone of throwaway messages: thumbing through the detritus of a culture increasingly caught in a web of inconsequential moments.

If the need for personal mobility arises, the protocols of this addiction usually require a device clutched in the right hand, ready to receive an incoming “message.” The left hand is the withering appendage still used to carry whatever else must also come along.

There can be no doubt that a portable phone has all kinds of useful functions for journalists, travelers, business people, and many of the rest of us. But it has become an easy reason to postpone more demanding tasks. We are too ready to divert our attention to screens of minor delights. Even counselors and psychotherapists are now advised to tolerate mid-session phone-checking from their younger clients, who now average well over 100 hits a day (Psychotherapy Networker, November, 2018).

There can be no doubt that a portable phone has all kinds of useful functions for journalists, travelers, business people, and many of the rest of us. But it has become an easy reason to postpone more demanding tasks. We are too ready to divert our attention to screens of minor delights. Even counselors and psychotherapists are now advised to tolerate mid-session phone-checking from their younger clients, who now average well over 100 hits a day (Psychotherapy Networker, November, 2018).

Consider a brief sampling of what this overuse is costing us.

–Intrapersonal thought is impaired. We are not the people we should be if we don’t consider our actions and decisions. The work of a fully functioning human includes examining the events and moments in our lives. Plato’s reminder that “an unexamined life is not worth living” is self-evident. We need time to hear ourselves in order to set our own compass for the days and weeks ahead. While many are proud to cite their devotion to yoga or meditation, the concentration and sustained awareness they can produce used to be a common experience for previous generations. The natural rhythms of the pre-digital world gave individuals a natural window to their consciousness.

A spectator’s world is one where things happen to them; where the screen is to be seen; where reaction dominates over action.

–Time is lost on tasks that could be more innovative, creative and educational. We seem to turning into the kinds corpulent and devoted spectators that populated Pixar’s prescient WALL-E (2009). A spectator’s world is one where things happen to them; where the screen is to be seen; where reaction dominates over action. Since creativity and innovation require sustained attention to a single task, we must nurture the capacity for such linear thinking. How many symphonies would Joseph Haydn have written if his pocket held an iPhone 8? He wrote over a hundred in his lifetime, but I doubt he would have made it even to the Farewell Symphony, Number 45.

–Personal identity that needs to form and evolve is put under siege. We can easily succumb to the seemingly happier but mostly inflated self-presentations offered by others. Evidence from recent studies suggests that many adolescents tend to fall into lower levels of self-esteem if they are heavy users of social media. (Journal of Adolescence, August 2016, 41-49). This is probably because online communities like Instagram tend to norm what’s “cool” and what’s not. The resultant checking of self against others drains away the natural impulse to shape one’s identity to passions found in the inner self.

–Real-time contact with others is decreased. For many of us, rates of daily “screen time” have crept into the eight hour range. Phones make up about half of that time. Researchers have also documented a disturbing recent trend indicating that middle and high school students are avoiding actual interaction with strangers or adults. For them, face-time with all but a best friend is stressful. More perversely, as recently noted, a phone has become its own excuse to not see or connect with another.

The new year is a good time to reconsider what matters. Phone culture is too often the cause of a downward spiral where ‘listeners’ no longer hear, observers no longer notice, and the rest of us are on the verge of becoming immune to the advantages of figuring out what we actually think.

![]()

This is obvious to any user of Facebook, Instagram or other forms of social media. Facebook dramatically displays images of ourselves and the things and images we will allow to stand in for us. Selfies in particular can become galleries presenting the self-conscious self. We also use social media to relay pieces of the culture that we want others to like as much as we do. Most of the time a post includes a moment when we at least ask ourselves the central curatorial question: Is this post worth my association with it?

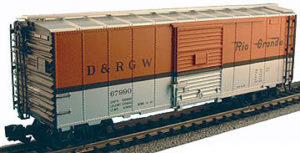

This is obvious to any user of Facebook, Instagram or other forms of social media. Facebook dramatically displays images of ourselves and the things and images we will allow to stand in for us. Selfies in particular can become galleries presenting the self-conscious self. We also use social media to relay pieces of the culture that we want others to like as much as we do. Most of the time a post includes a moment when we at least ask ourselves the central curatorial question: Is this post worth my association with it? And so we reach the communication angle. In some way a collection on display stakes a claim about who we are. It marks crucial antecedents. We use things to be proxies of our unique affinities and aspirations. I could bore you with the reason a large model Rio Grande Railroad boxcar is my own Renoir. But it’s enough to note that it sits on a shelf in a ‘man cave,’ ready to be the trigger for a story that is almost never requested.

And so we reach the communication angle. In some way a collection on display stakes a claim about who we are. It marks crucial antecedents. We use things to be proxies of our unique affinities and aspirations. I could bore you with the reason a large model Rio Grande Railroad boxcar is my own Renoir. But it’s enough to note that it sits on a shelf in a ‘man cave,’ ready to be the trigger for a story that is almost never requested.