More and more Americans are experiencing the social disorientation that comes with partial deafness. No longer just grandpa’s problem, its now a development affecting millions of younger Americans.

Imagine that you have a friend who has the unusual habit of glancing directly at the sun while they conversing with someone outdoors. That’s not a good thing. Obviously, the sun is too intense for sensitive eyes, a point we would surely make to the friend. A lifetime with such a habit will leave them with a host of eye problems, if not complete blindness.

Suppose you have another acquaintance who is rarely seen without lanyards hanging down from her ears. They are always present when she is commuting or working at her desk. Like millions, she would rather forget her purse than not having her ear buds with her. And because the sounds she listens to spill out beyond her ears, you can tell what music she likes.

In a sense, she is also looking into the sun. The volume level of her music is probably past a threshold where loudness so close to the ear is safe. Like one in three Americans, she on her way to hearing loss, which will mean that in a few years she will be struggling to connect in a wide variety of social settings.

Our dilemma is that we live in a loud world that our ears were not designed for. Think of noise as aural trash: stuff that piles up around us that we hardly notice less because it has no visual presence. But its there all of the time: at music concerts where the sound is punishingly loud, or in the everyday equipment of modern life like leaf blowers, hair dryers, vacuums, and hundreds of other sources. Previews shown in movie theaters, for example, regularly play at about 100 dB: only slightly less than standing at the end of an airport runway. With this kind of noise, a person’s hearing will deteriorate over time. There are bones in the middle ear to protect us from loudness. But they are no match for what we throw at them.

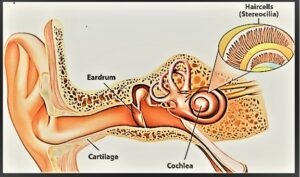

Loud sound destroys the microscopic stereocilia–tiny thin cells–in the cochlea within the inner ear. They do the important work of converting sound pressure waves into nerve impulses sent to the brain. One scientist studying the cilia of a nearly deaf person said they looked like a forest of trees that had been blown over in a storm. But unlike a forest, they usually will not regrow.

Loud sound destroys the microscopic stereocilia–tiny thin cells–in the cochlea within the inner ear. They do the important work of converting sound pressure waves into nerve impulses sent to the brain. One scientist studying the cilia of a nearly deaf person said they looked like a forest of trees that had been blown over in a storm. But unlike a forest, they usually will not regrow.

New research points out that there are significant costs for those who have lost even a fraction of their listening acuity. With hearing loss, clinical dementia increases by 50 percent and depression by 40 percent. Overall, participants in some studies report increased feelings of isolation and disconnectedness, as documented by a reporter recounting the story of one 68-year-old woman.

[H]er world began to shrivel. She stopped going to church, since she could no longer hear the sermons. She abandoned the lectures that she used to frequent, as well as the political rallies that she had always loved. Communicating with her adult sons became an ordeal, filled with endless requests that they repeat themselves. Now considered as hazardous as smoking 15 cigarettes a day, loneliness vastly raises the risks of depression, dementia and early death.

Your ears will not send messages that they are being forced into a destructive death spiral. You need to be motivated enough to protect them. Exercise a few simple precautions to stave off hearing loss.

- Always wear ear protection at arena concerts and even professional sporting events. In my recent book, The Sonic Imperative, I reported that one baseball stadium nearby is equipped with 1400 loudspeakers. Fans notice that noise at a game is frequently over the top, since the sound system is programmed like a dance club.

- Always wear ear protection when using power equipment like lawnmowers, lawn trimmers, leaf blowers and even vacuum cleaners and hunting rifles. I use a comfortable 21-dollar 3M over the ear headset. There are even many with Bluetooth speakers in them: an incredibly dumb idea.

- Carry a clean pocket tissue. When an event turns into an unexpected auditory assault, such as in a movie theater or noisy bar, it pays to have a piece of tissue that can be crushed and placed at the entrance of the ear canals, temporarily muting the racket.

- When listening to music, playing games or watching videos, learn to set aside the mistaken belief that louder is always better. Heed the cautions that come with portable audio players. In many cases, loudness creates unpleasant distortion and listening fatigue.

- Teach your children about the fragility of hearing. We know from studies that teens will reject requests to ‘turn it down.’ The message needs to come earlier.

The ability to hear is a wonderful gift, and modern applications of sound are full of interesting surprises. For more insights see The Sonic Perspective: Sound in the Age of Screens, available at a low price from Amazon.com.

![]()