[My confidence in 2015 that we have nothing to fear from Artificial Intelligence may look distinctly antique in light of the warnings now coming from A.I. researchers. Even Elon Musk is calling for a moratorium in the implementation of dense generative language systems that can replicate the words, sounds and images of humans. Maybe the confidence expressed in the piece below is a tad high. And my examples are dated. But let me take a minority view and argue that most of the claims made below still hold. We can now surely pass off good fakes. Humans have always had a knack for that. But it remains true that machines and software lack a self. What is essential to the human experience is our natural impulse to interpret others. This capacity has no meaningful counterpart in machine-generated language; machines lack the features of human character that always give our thoughts tendencies. We are interpreters more than recorders of our world.

[My confidence in 2015 that we have nothing to fear from Artificial Intelligence may look distinctly antique in light of the warnings now coming from A.I. researchers. Even Elon Musk is calling for a moratorium in the implementation of dense generative language systems that can replicate the words, sounds and images of humans. Maybe the confidence expressed in the piece below is a tad high. And my examples are dated. But let me take a minority view and argue that most of the claims made below still hold. We can now surely pass off good fakes. Humans have always had a knack for that. But it remains true that machines and software lack a self. What is essential to the human experience is our natural impulse to interpret others. This capacity has no meaningful counterpart in machine-generated language; machines lack the features of human character that always give our thoughts tendencies. We are interpreters more than recorders of our world.

There is another problem in the current hand-wringing that I have seen. Everyone seems to be describing humans as information-transfer organisms. But, in truth, we are not very good at creating reliable accounts of events. What we seem hardwired to do is to communicate our understanding of events around us. Human understandings come from prior experience. For example, does a chatbot “like” the music of Franz Joseph Haydn? I could care less. Judgments and understandings about human products must be made by other humans.]

We are awash in articles, books and films about the coming age of “singularity:” the point at which machines will supposedly duplicate and surpass human intelligence. For decades it’s been the stuff of science fiction, reaching perhaps its most eloquent expression in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 motion picture, 2001: A Space Odyssey. The film is still a visual marvel. Who would have thought that Strauss waltzes and images of deep space could be so compatible? Functionally, the waltzes have the effect of juxtaposing the familiar with a hostile void, making the film a surprising celebration of all things earthbound. But that’s another story.

The central agent in the film is the HAL-9000 computer that begins to turn off the life support of the crew during a long voyage, mostly because it “thinks” the humans aren’t up to the enormous task facing them.

Kubrick’s vision of very smart computers is also evident in the more recent A.I., Artificial Intelligence (2001), a project started just before his death and eventually brought to the screen by Steven Spielberg. It’s a dystopian nightmare. In the film intelligent “mechas” (mechanical robots) are generally nicer than the humans who created them. In pleasant Haddonfield New Jersey, of all places, they are shot on sight for sport.

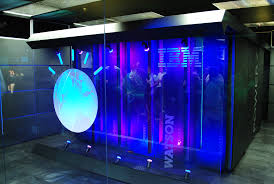

Fantasies of machine intelligence have lately given way to IBM’s “Big Blue” and “Watson,” mega-computers with amazing memories and—with Watson—a stunning speech recognition capability that is filtering down to all kinds of devices. If we can talk to machines, aren’t we well on our way to singularity?

For one answer consider the Turing Test, the challenge laid down by the World War II code-breaker Alan Turing. A variation of it has been turned into a recurring world competitions. The challenge is to construct a “chatterbot” that can pass for a human in blind side-by-side “conversations” that include real people. For artificial intelligence engineers, the trick is to fool a panel of questioners at least 30 percent of the time over 25 minutes. According to the BBC, a recent winner was a computer from the University of Reading in the U.K. It passed itself off as a Ukrainian teen (“Eugene Goostman”) speaking English as a second language.

Machines Lack a Self

In actual fact, humans have nothing to fear. Most measures of “human like” intelligence such as the Turing Test use the wrong yardsticks. These computers are never embodied. The rich information of non-verbal communication is not present, nor can it be. Proximate human features are not enough. For example, Watson’s “face” in its famous Jeopardy challenge a few years ago was a set of cheesy electric lights. Moreover, these smart machines tend to be asked questions that we would ask of Siri or other informational databases. What they “know” is often defined as a set of facts, not feelings. And, of course, these machines lack what we so readily reveal in our conversations with others: that we have a sense of self, that we have an accumulated biography of life experiences that shape our reactions and dispositions, and that we want to be understood.

Just the issue of selfhood should remind us of the special status that comes from living through dialogue with others. A sense of self is complicated, but it includes the critical ability to be aware of another’s awareness of who we are. If this sounds confusing, it isn’t. This process is central to all but the most perfunctory communication transactions. As we address others we are usually “reading” their responses in light of what we believe they already have discerned about us. We triangulate between our perceptions of who we are, who they are, and what they are thinking about our behavior. This all happens in a flash, forming what is sometimes called “emotional intelligence.” It’s an ongoing form of self-monitoring that functions to oil the complex relationships. Put this sequence together, and you get a transaction that is full of feedback loops that involve estimates if intention and interest, and—frequently—a general desire born in empathy to protect the feelings of the other.

It’s an understatement to say these transactions are not the stuff of machine-based intelligence, and probably never can be. We are not computers. As Walter Isaacson reminds us in his recent book, The Innovators, we are carbon based creatures with chemical and electrical impulses that mix to create unique and idiosyncratic individuals. This is when the organ of the brain becomes so much more: the biographical homeland of an experience-saturated mind. With us there is no central processor. We are not silicon-based. There are the nearly infinite forms of consciousness in a brain with 100-billion neurons with 100-trillion connections. And because we often “think” in ordinary language, we are so much more—and sometimes less—than an encyclopedia on two legs.

![]()

The growth of technology for communication at a distance allows a person to grow comfortable with digital isolation. But it comes at a price we all have to pay. The gamer cum intelligence leaker Jack Teixeira followed what is becoming a familiar pattern of the withdrawal of some young males from a balanced life. He was a member of the Air National Guard, but reportedly found his personal niche playing online games, and trying to be what the Washington Post described as a “commanding persona online.” We now know that his desire to make his mark—even at a distance—involved passing on a trove of U.S. secrets. His distorted way to dramatize his worth required no social skills, and apparently no sense of connectedness and responsibility to the people damaged by his intelligence leaks. All he needed was a video monitor facing a plush game chair a few feet away.

The growth of technology for communication at a distance allows a person to grow comfortable with digital isolation. But it comes at a price we all have to pay. The gamer cum intelligence leaker Jack Teixeira followed what is becoming a familiar pattern of the withdrawal of some young males from a balanced life. He was a member of the Air National Guard, but reportedly found his personal niche playing online games, and trying to be what the Washington Post described as a “commanding persona online.” We now know that his desire to make his mark—even at a distance—involved passing on a trove of U.S. secrets. His distorted way to dramatize his worth required no social skills, and apparently no sense of connectedness and responsibility to the people damaged by his intelligence leaks. All he needed was a video monitor facing a plush game chair a few feet away.