The eye has now fully extended its dominance over the ear, occasionally with interesting results.

The idea that some people are “visual learners” is an old one. But this observation has special relevance in our age where more media content comes to us in packages meant to be seen as much as read. What this means in its simplest form is that to see is to know. We understand something as meaningful if it comes to us as an image or in a visual frame. For example, there is new research that indicates that anti-smoking warnings on cigarette packages that include graphic pictures slightly increases the willingness of smokers to quit.

There are obvious and sometimes crippling disadvantages to the idea visual knowledge. Pictures are usually poor at capturing ideas: one reason that local television news often lives up to the dismissive phrase of a “vast wasteland.” “If it bleeds it leads” is the old phrase that suggests the narrow focus. But for the moment let’s be more positive. As various visual theorists have reminded us, “presentational media” have the advantage of no “access code.” We don’t have to be literate to understand feelings and impressions given off by photographs or images.

Appropriation of a visual meme can equal stealing a sacred text.

Television as a pervasive daily presence has certainly played its part in making us ocular-centric. This shift dates from the 1950s, when it became a household necessity. The new screen in the living room meant that family life would be changed forever. A second milestone in moving toward the visual was the consequential decision by Apple’s Steve Jobs to borrow (steal?) a Xerox research lab’s idea to use graphical interfaces for computers: what we know as the colorful icons and “windows” that present web content with store-window vividness. Add in video recording, DVD’s and easy-to-use cameras, and the transition to visual formatting of content was complete. Especially for younger Americans, the eye has fully extended its dominance over the ear, to the extent that people will sometimes accept bad sound even while they watch super high definition video images. It’s no surprise that the recent Pepsi ad campaign trading on the images of protest looked bad to so many people. Appropriation of a visual meme can equal stealing and co-opting a sacred text.

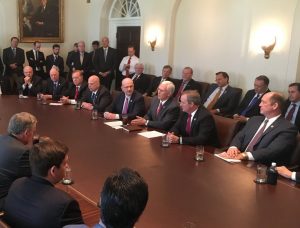

People with good visual acuity can sometimes see what the rest of us might miss. That was surely the case with many readers of a 2017 New York Times column where Jill Filipovic asked us to take a closer look at a recent White House photo of a meeting of the “Freedom Caucus” members of the House of Representatives. Vice President Pence posted the photo (above), proudly noting that deliberations were underway to replace the Affordable Care Act. No woman appeared in the photograph. What Pence saw as a fitting representation of orderly deliberation Filipovic understood as a representation of unabashed sexism:

For liberals, the photo seemed like an inadvertent insight into the current Republican psyche: Powerful men plotting to leave vulnerable women up a creek, so ensconced in their misogynistic world that they don't even notice the bad optics (not to mention the irony of the "pro-life" party making it harder for women to afford to have babies).

Filipovic went on to argue that that this male power play and its image was evidence of a powerful misogynistic streak. And we can only applaud her ability to see what some of us otherwise might not have noticed. Reproductive issues are only some of many other concerns that uniquely affect a woman’s health. White and well-heeled men have been occupying dominant decision-making roles for so long that we may not “see” the gender majority excluded from the room. Thanks to her sense of visual acuity, the group’s decision-making monopoly and hypocrisy looks even worse.