We can’t afford to not teach the humanities, which collectively help us understand why we should want to be part of a great society.

The core academic centers of humanistic study in the nation’s universities are reeling from consecutive blows inflicted first by Covid, then by the meddling of The Trump administration, and, finally, by states like Texas and Florida which seek to impose censorship on scholarship and curricula. Because of these threats to funding students entering the university have fewer options than was true even a decade ago.

The social sciences and humanities thrive when open and eager minds can share the same space. As the effects of Covid isolation in 2019 made clear, it is our birthright as learners to be with others. For college students this means being in the presence of an effective instructor in any field that creates insight about what is possible and what’s at stake within human communities. Humanities courses built around groups of students remind us where we have been and where collective debate and discussion can still take us.

![]() Programs in writing, philosophy, performance studies, history, foreign languages, music, dance, theater, journalism and rhetoric have sometimes been closed consolidated. Recent news reports make it apparent that the problem is more than Covid. Scholars in the social sciences and history have come under attack because of the malignant idea that teaching subjects relevant to challenges raised by gender, income stratification, and race are “woke” and not sufficiently “pro-American.” It is bad enough when anti-intellectual office holders take pleasure in pushing American universities to become trade schools. It is even worse when the power of a state is used to prohibit the teaching of history and social theory that help explain the complex fabric that is the nation’s past and uncertain future. Recently, myopic leaders at Texas A and M University have dictated that a college course dealing with theories of race or gender must first be cleared through the President’s Office. That’s an awful precedent, and a violation of a long tradition of faculty self-governance. Astonishingly, Florida’s political leaders even question the legitimacy of the social sciences, especially sociology.

Programs in writing, philosophy, performance studies, history, foreign languages, music, dance, theater, journalism and rhetoric have sometimes been closed consolidated. Recent news reports make it apparent that the problem is more than Covid. Scholars in the social sciences and history have come under attack because of the malignant idea that teaching subjects relevant to challenges raised by gender, income stratification, and race are “woke” and not sufficiently “pro-American.” It is bad enough when anti-intellectual office holders take pleasure in pushing American universities to become trade schools. It is even worse when the power of a state is used to prohibit the teaching of history and social theory that help explain the complex fabric that is the nation’s past and uncertain future. Recently, myopic leaders at Texas A and M University have dictated that a college course dealing with theories of race or gender must first be cleared through the President’s Office. That’s an awful precedent, and a violation of a long tradition of faculty self-governance. Astonishingly, Florida’s political leaders even question the legitimacy of the social sciences, especially sociology.

What happened at the once-innovative New College in Sarasota is instructive. Since being taken over by neanderthals in Tallahassee, the four-year graduation rate has fallen. The school’s U.S. News college ranking has been downgraded significantly. Its honors college philosophy has mostly been abandoned, and faculty and students have left. There is now talk of simply closing down this once-prized liberal arts institution.

What happened at the once-innovative New College in Sarasota is instructive. Since being taken over by neanderthals in Tallahassee, the four-year graduation rate has fallen. The school’s U.S. News college ranking has been downgraded significantly. Its honors college philosophy has mostly been abandoned, and faculty and students have left. There is now talk of simply closing down this once-prized liberal arts institution.

A newly graduated academic looking to start a career in a Florida or Texas university would do well to consider the Faustian bargain of signing on to institutions where curricula decisions have been taken over by a governor or state legislature. Disturbingly, stretched parents have abetted this trend by having second thoughts about spending money on any undergraduate curriculum that offers a palette of experiences larger than what they imagine is required to hold a single job. Writer Julie Schumacher reminds us what her English majors can accomplish: “Be reassured: the literature student has learned to inquire, to question, to interpret, to critique, to compare, to research, to argue, to sift, to analyze, to shape, to express.”

Weakening the humanities is akin to disarming voters who need to put up a full defense of democratic values. They might benefit from knowing why Plato and his student, Aristotle parted ways on the usefulness of public opinion. We can’t afford to not have the humanities, which collectively help us understand why we should want to be part of the kind of great and ethical societies based on law and argument that Aristotle imagined.

Weakening the humanities is akin to disarming voters who need to put up a full defense of democratic values. They might benefit from knowing why Plato and his student, Aristotle parted ways on the usefulness of public opinion. We can’t afford to not have the humanities, which collectively help us understand why we should want to be part of the kind of great and ethical societies based on law and argument that Aristotle imagined.

All if these attacks on academic institutions are a warning to parents that they are going to have to be selective in demanding more than a winning football team when schools come calling to sign up their college-ready offspring.

![]()

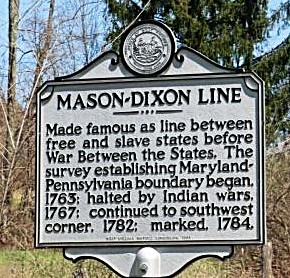

It is worth considering the idea that large nations may be too big to fail, but also too big to thrive as open societies.

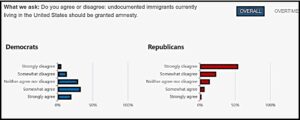

It is worth considering the idea that large nations may be too big to fail, but also too big to thrive as open societies. As a thought experiment, it is worth considering the thesis that large states may appear to be too big to fail, but they may also be too big to thrive as open societies. No one living in one of the geographical giants with huge land masses and understandably diverse populations can call them fully “unified.” This seems so obvious now. Though pollsters caution against assuming that the American population is as polarized as its current politics, it is still clear that regional differences have turned into regional antagonisms that weaken the chances to establish a good society.

As a thought experiment, it is worth considering the thesis that large states may appear to be too big to fail, but they may also be too big to thrive as open societies. No one living in one of the geographical giants with huge land masses and understandably diverse populations can call them fully “unified.” This seems so obvious now. Though pollsters caution against assuming that the American population is as polarized as its current politics, it is still clear that regional differences have turned into regional antagonisms that weaken the chances to establish a good society.